Value Investing: From Graham to Buffett and Beyond

In this blog post, I will be providing a book summary on Professor Bruce Greenwald's book Value Investing: From Graham to Buffett and Beyond (2021). In this book, Professor Greenwald explores the modern extention to value investing to successfully adapt with the changing economic and financial conditions.

Economy activity, which has shifted from

industry/manufacturing to services, has seen greater value placed on

intangible capital relative to tangible capital. Hard asset-based businesses are becoming less important. Professor Greenwald addresses this paradigm shift, showing us how to gain an analytical advantage, how to think about valuations and the way to quantify growth.

Gaining an Edge by Specialisation

- Either by design or practice, investors must specialise. Specialisation is the the most obvious way to improve the odds of being on the ride side of the trade. Investors have generally performed better starting from a very narrow focus and working outwards. Warren Buffett in a classic example of this and has been more successful investing in insurance, banking, old media, and consumer non-durables than in other industries.Those who try to be experts in many industries, usually took quickly, tend to be the jack of all trades but the master of none.

- Specialise in a particular geography. Focusing on firms with a

particular region is an advantage particularly for those who in invest in small

to medium sized companies. For services companies, it is just much easier

to monitor customers, suppliers, competitors, etc. It is also easier to

gain access to management.

- Spend at

minimum 1,000 hours or more to develop a decent working knowledge of an

industry. This is the equivalent of at least a full year to achieve an adequate

level of mastery. This has to be continuously deepened to increase

specialisation and to keep up with developments.

The Existence of Value Anomolies

Since the dawn of time, humans have developed behavioural tendencies to help them with survival. However, some of these traits today cause that cause these opportunities to exist in the markets. Professor Greenwald simplifies them into 3 three tendencies:

- The

"lottery ticket" appeal. People are prone to overpaying, despite

the unfavourably stacked odds, for the dream of getting rich quickly. In

the world of equity investing, glamour growth stocks represent these

lottery tickets.

- Loss aversion.

This is the direct inverse to the preference for lottery ticket. In

moments of market melt downs, people are more inclined to react and sell

without careful analysis to avoid further losses.

- Overconfidence.

People tend to embrace certainty and ignore alternative possibilities.

This bias intensifies the overvaluation of glamour stocks. In bad times,

people are overconfident in their pessimism, which leads to

undervaluations.

Discounted Cash Flows

Professor Greenwald characterises Discount Cash Flows (DCFs) as a method with several fundamental problems.

- It ignores the balance sheet.

- Terminal value dominates the overall value.

- Minor adjustments to inputs often creates a

large range in potential valuations.

DCFs are good for

projects/events over the short-term with greater cash flow visibility. These

include takovers, corporate reognisations, bankruptcies, etc.

- Including the balance sheet.

- Organise the components of value by

reliability with which they can be estimated.

- Make clear the assumptions for estimated

levels and components of value.

Instead, Professor Greenwald teaches business valuation using a 3 element approach: Asset Value, Earnings Power and Growth.

Asset Value

Asset Value (AV) is the most reliable source of valuation data.

If the company future does not look economically viable, use liquidation value.

If the company is a going concern, use reproduction cost. Reproduction cost is the sum required to reproduce the company. This requires adjustments of balance sheet items, recognition of costs that have been expensed over the years which have added to the cost required for a competitor to build the same company of exact calibre, e.g. R&D spend, marketing spend, etc.

For products, converting R&D spending into a valuation of a company's product portfolio is most simply done by multiplying annual spending by the number of years of R&D embodied in the company's product line.

Earnings Power Value

Earnings Power is the sustainable current earnings that are constant over an indefinite future. Earnings Power Value (EPV) capitalises this value by dividing this value by the cost of capital. EPV does not attempt to anticipate future changes in a company's operations. The formula equation for EPV is

EPV

= Earnings Power × 1/R

where R is the constant future cost

of capital.

Sustainable current earnings are

earnings measured after making the necessary investments to return a company's

operations at the year's end to the same condition it was at the start of the

year, essentially like Warren Buffett owners' earnings.

In this calculation, we will have to omit the following growth capital

expenditure and non-recurring items.

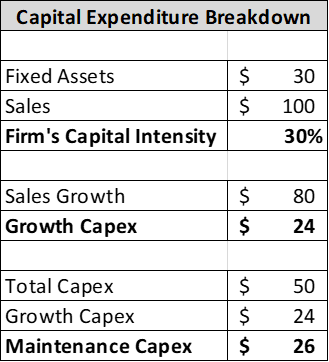

To segregating growth from maintenance capex, Professor Greenwald uses the following calculation:

- Firm's Capital

Intensity = Fixed Asset/Sales. Normalise over an appropriate time period.

- Firm's Capital Intensity × Growth in Sales =

Growth Capex

- Maintenance

Capex = Total Capex - Growth Capex

The way to calculate the sustainable operating earnings is to:

- Start with the revenue.

- Multiple by an average level of

operating/EBIT margins, ideally encompassing two business. cycles. Do not apply higher profit margins when

margins are growing and vice versa.

- Adjust for unconsolidated operations,

e.g. investment in associates.

- Calculate NOPAT by adjusting by the average tax rate, i.e. EBIT(1 - Tax Rate).

To calculate cost of capital, estimates can be used using the different asset classes available. The cost of equity using this method is based on the security markets line. If yields are 5% on investment grade (at least BAA rated) and venture capital is 13 and 14%, cost of equity is between 6 and 13%. The lower the rates, the lower the cost of equity. Based on this assumption, the typical range of values for the cost of equity can apply to companies of varying risks.

Low risk typically entails non cyclicals such as utilities and high risk typically entails cyclical and commodity type businesses. Having selected a cost of equity, a cost of capital can be calculated using the weights of the debt and equity components, adjusting the cost of debt for tax.

The final step in determining EPV is to divide the estimated earnings power by the estimated cost of capital. This value will essentially give you an enterprise value. To arrive at the equity value, net debt must be subtracted. 0.25 - 0.5% revenue should be considered as working capital and should not be included in net debt.

Growth

Great companies are the ones that can

pay out cash to its investors even as it funds its growth and these companies

are rarely priced favorably. They often represent get rich quick stocks for

which many investors repeated overpay. However, with prudent and skillful

application, these stocks can be bought.

Graham and Dodd never paid extra for

growth. They based stock purchased decisions based on EPV and any growth was

considered free; this was their margin of safety.

These are some points to consider about growth stocks:

- They are optimistically forecasted and

therefore suffered from being systematically biased. Growth high flyers

generally disappoint and slow growers exceed expectation. Do not fall into

the pitfall of relying on projections.

- Growth stocks will be usually overpriced

when the companies do not have a competitive advantage. Strong growth does

not necessarily ensure enduring compounded growth and creation of a moat.

It will attract competitors that will in turn, erode growth and

profitability enjoyed by a first mover; late entrants are not materially

disadvantaged if there are low barriers to entry. Sooner or later, if

every competitor will earn only its cost of capital at best. Without competitive advantages and barriers to entry, growth will create little or

no value.

- For a company to enjoy

long-term competitive advantage and high profitability, a telling

sign is when growth rates are accompanied by high and stable or growing

ROICs.

- It's not all about the

growth rate. How much cash investments are required to support the growth?

Growth in virtually every instance requires additional investments, and

that investment must be paid for. The crucial question for

determining the net value of growth for a company is the relationship

between the amount of investment needed to pay for the growth compared

with the additional amounts and timing of distributes that the growth may

produce. Buffett uses the analogy to describe this concept, "a bird in the hand is worth

two in the bush."

- Growth

that require no supporting investment is extremely rare.

An investment based on a firm's prospects for growth must satisfy the two requirements:

- The growth must create value. This means

that they must earn more than their cost of capital.

- Not all growth can be appraised with enough precision to permit an accurate valuation.

The 2 different markets where companies can enter and earn returns:

- The highly profitable market. In these

markets, incumbents enjoy sustainable competitive advantages; this is the

worst for potential new entrants. Profitability is the result of the

sustainable competitive advantages that ultimately rest on economies of

scale. This makes it difficult for new entrants to earn above their cost

of capital. Any growth for a firm operating at a competitive advantage or

one with low quality management will destroy value. i.e. if they earn 5%

their cost of capital per year, for example, $5m, and the cost of capital

is 10%, $50m worth of value is being destroyed every year.

- A new market. Growth can create value

for firms entering new markets where it can dominate in the future. Here,

they have the opportunity to build out their sustainable competitive advantage and bring up

barriers to entry.

So when does growth create value?

- The value of organic growth that is

driven by increasing market demand as distinguished from growth that is

actively pursued by the firm. Only firms in markets protected by barriers

to entry will organic growth lead to

sustained value creation.

- The consequences of

other favorable developments, such as new technologies that reduce costs

and lead growth in earnings even if they do not directly crease demand.

The common ones are lower costs and innovations in marketing, and enhanced

distributions that increase operating efficiencies.

- The value of growth

options, secondary opportunities that a company can pursue if warranted

and avoid if unattractive. Without barriers to entry, growth avenues that

aren't protected by barriers to entry have the potential growth benefits

offsets by the negative effect of fierce incoming competition.

- The consequences of

market shrinkage as opposed to expansion. If a market is shrinking,

economies of scales will decline, adversely affecting margins through

operating leverage.

- The differences

between growth in core markets compared to growth in new markets.

- Focus on core regions

that a company already dominates and build a moat there, slowly building

out around the edges.

- Otherwise, enter

markets where there are no existing dominant competitors who have both

captive customers and economic of scale advantages. Firms seeking to

dominate these virgin markets must be extremely disciplined - focus on

one market at a time - and superb at the execution.

Questions to ask for growth when evaluating:

- Is EPV > AV? This attracts

competitors until EPV = AV.

- Does it operate in a market where it has

sustainable competitive advantage?

- Does it currently earn above its cost of

capital?

- Is it likely to make growth investments

in current or adjacent markets to which its competitive advantage can be

extended?

Franchise

businesses are the companies that have EPV well above AV. This is summarised in the table below:

There is no good

businesses in a competitive environment with relentless change.

Good businesses steadily earn returns of 15-20% or more by these measures outlined below, well above the typical 10% cost of capital. These returns should increase than erode over time. Good businesses are also ones that grow:

- Return on equity

- Return on capital

- After-tax returns on capital

First movers have been no better than

companies with esteemed brands in achieving sustainable competitive advantages

and the profitability that we expect from good businesses.

Any enhancements to a generic product

or service without a protected differentiated difference will invite

competition to come in, eat up returns until the EPV equates to the AV.

Sustained

competitive advantages in the business world are therefore the exception rather

than the rule.

To create this exception, Professor Greenwald suggests that there are

moats which have differing degrees of strength:

- Law: this is the strongest.

Government privileges such as licenses, patents,

copyrights, or other protections.

These are the cable franchise, broadcast television

stations, telephone companies and electric utilities. These all enjoy exclusive

local franchises. However, governments can sometimes regulate these entities so

that there are elements of price and profit controls, hindering the opportunity

to earn excess returns.

- Cost: how good are management and does the business benefit from size?

- Cost advantage from economies of scale

or proprietary technology. Proprietary technology is most useful in slow

moving industries, whereas in fast, proprietary technology becomes

redundant rather quickly.

- Know-how. As an business gains

experience, the entrants will always trail the incumbent in the necessary

expertise it takes to make this efficiently. To would depend on who the

incumbents are in the industry. The test here is whether the required

technology, including the human-based skill, is accessible to the entrant

on the same terms as it is to the incumbent. e.g. Mercedes has a good

brand, but its ability to attract talent is no less than its peers.

- Revenue/customer demand advantages: how do you keep your customers captive?

- Habit, usually associated with high

purchase frequency. This is probably the most powerful, since it

reinforces the habit with every purchase or consumption.

- Search costs. If the cost of searching

for an alternative to the existing product or service is high, customers

will have an aversion to change. This is a form of loss aversion which

takes the form of potential negative experience using a new product or

service.

- High switching costs. This form of

customer captivity is also a form of loss aversion which takes the form of

potential increase in error rates as the new installation is implemented.

Most common competitive advantages are regional or product line economies

of scale equates to local share or niche. Geoff Ganon from Focused Compounding

states location as the number one competitive advantage a company can have due

to its ability to avoid global competition.

A competitive advantage ultimately

defends its position depends on the degree of customer captivity and/or

customer inertia (or the rate at which the customer habits are

solidifying).

Assessing competitive advantage includes the following assessment of the checklist items.

Quantifying Growth

Identifying these companies is half the task, the other half involves the valuation.

Professor Greenwald argues that the intrinsic value of growth can not be calculated with enough accuracy to be deemed useful. Minor directional changes in inputs can cause significant margins of error. Instead, Professor Greenwald suggests using an estimated return from buying a growth security at its current market price, and comparing that to the alternative opportunity sets.

The key value-determining factors are:

- Current earnings power.

- Distribution-retention policy for earnings.

- Organic growth rates in revenue and margins.

- Net Working Capital/Sales. This is the amount required in net working capital to fund organic growth, i.e. if an additional $1 of sales requires $0.5 in additional NWC, an additional $5 dollars of sales will require $2.5 in NWC as an investment towards organic growth.

- Inorganic growth/active investment. The value creation factor is the return multiple on the undistributed earnings above cost of capital, i.e. 30% ROIC vs 10% cost of capital means the value creation factor is 3. The most difficult is the value created by active investment, although it is less significant for companies that regularly distribute 85% or more of their earnings, leaving little to invest.

- Franchise fade rates. This is the rate at which the moat fades over time. If the time to business extinction is 50 years, the annual fade rade is approximately 72/50 or 1.4%. For durable franchises like Coca-Cola, this might be 80 years. For more recent tech companies, it might be more brief at 15 to 20 years.

- The cost of capital.

Assessing Management Performance

- Achievement of operational efficiency

both in controlling costs and in the areas such as marketing and product

development. This one is by far the most important area. Achieving

excellence in this area is like a marathon, where it requires constant

attention to incremental improvement.

- The strategy for growth, especially

capital allocation, which should avoid growth for its own sake and focus

on those opportunities in which growth creates value. On growth that

produces returns above their cost of capital creates value.

- Financial structure and the distribution

of cash flow to investors.

- Human resource management.

The migration of business activity from manufacturing to services has meant that the standard accounting measures are becoming less relevant towards calculating intrinsic value.

To a large degree, the assets of good and great businesses of today are mainly intangibles which comprise of product portfolios, brands, customer relationships, trained workers and organisational structures. These items are expensed and do not appear on the traditional balance sheet, making it important to consider when basing a firm's intrinsic value on assets, calculating a firm's sustainable earnings and its potential growth.

The 3-elements to valuations can be summarised in the diagram below.

Comments

Post a Comment